When the Wisconsin territorial legislature created St. Croix County in 1840, the county seat was placed by popular vote at Stillwater, a thriving lumber community on the west bank of the St. Croix River. But in granting Wisconsin statehood in 1848, the legislature excluded land west of the St. Croix, designating it as part of Minnesota Territory. The redrawn St. Croix County had a new county seat at St. Croix Falls in the future Polk County. The county board of commissioners then moved to divide St. Croix County into three townships, the southernmost of which was Elizabeth.

Settlement in Elizabeth Township was typical for the northwestern part of the state in mid-century. Newly arrived settlers were not farmers exclusively, though most had to farm to survive. They were ministers, teachers, livery and ferry operators, undertakers, woodworkers, millers, masons, bricklayers, and retailers. Grist millers claimed land along nearly every stream that had enough water to dam, create a mill pond, and turn a water wheel for power. The swath of timberland known as the Big Woods in the township’s eastern third attracted sawmill operators eager to turn its abundance of pine, beech, oak, butternut, and rock elm into lumber for construction.

In the five years between 1848 and 1853, the trading post at Mouth of the St. Croix was part of a growing village and steamboat destination. The population of settlements at El Paso, Greenwood (River Falls), Maiden Rock, Martell, Plum City, and Rock Elm Center grew steadily, creating new business and leadership opportunities for residents and prospective settlers. People invested in general stores, livestock brokerages, livery services, and boarding houses. They collaborated on church, school, and cemetery organization, land clearing, timber harvesting, and road building. Elizabeth Township leaders began to see benefits in reorganization.

An application for countyship was approved by the state legislature on March 14, 1853. Elizabeth Township boundaries became the boundaries of a new county named after the 14th U. S. president, Franklin Pierce. In an election the following November, the board of supervisors of the now former Elizabeth Township became the new Pierce County board. The community called Elizabeth was renamed City of Prescott, and with its growing population and visibility, was the obvious choice for county seat. The first county courthouse was located there in a brick house that still stands on Dakota Street.

Communities in all parts of Pierce County thrived as a result of the land speculation and immigration of the mid 1850s. The county board addressed its first petition for new township formation in January 1854. Settlers and speculators trekked to the nearest land office in Hudson, and the county’s population approached 5,000. By 1860, eleven new townships had been organized—Martell, Isabella, Trimbelle, Diamond Bluff, Clifton, Oak Grove, Perry, Pleasant Valley, Hartland, Trenton, El Paso, and River Falls. And a newly formed agricultural society was planning the first Pierce County Fair.

Communities in all parts of Pierce County thrived as a result of the land speculation and immigration of the mid 1850s. The county board addressed its first petition for new township formation in January 1854. Settlers and speculators trekked to the nearest land office in Hudson, and the county’s population approached 5,000. By 1860, eleven new townships had been organized—Martell, Isabella, Trimbelle, Diamond Bluff, Clifton, Oak Grove, Perry, Pleasant Valley, Hartland, Trenton, El Paso, and River Falls. And a newly formed agricultural society was planning the first Pierce County Fair.

During this same decade, the Ojibwe and Dakota peoples, who frequented the eastern side of the Mississippi to hunt or gather medicinal and food plants, encountered few problems with Pierce County settlers. More than a few diaries mention peaceful, though misunderstood, bi-cultural encounters. And little public attention seems to have been given to men like Philander Prescott who married native women and had mixed blood children. But by 1860, federal government policies were keeping the Ojibwe farther north, and pressuring the Mdewakanton Dakota west of the Mississippi to abandon their traditional lands and join other Dakota bands in western Minnesota. Deliberate and inadvertent misapplication of regulations would soon lead to a Dakota uprising in Minnesota with rippling effects in Wisconsin.

As Pierce County settlement spread more than 25 miles from Prescott, some residents thought the county needed a more centrally located government. But disagreement among county board supervisors resulted in stalemate, leading the state legislature to authorize a popular vote to settle the matter. On March 15, 1861, just under two thirds of county voters favored moving the county seat to the village of Perry near the county’s geographic center. Growth in the county had slowed by the first year of Civil War, but concern was less about growth than about creating and keeping strong local economies. Though fewer than 400 Pierce County young men volunteered for service in Wisconsin regiments in the Union Army, patriotism showed itself in different ways. One way was renaming the village and township of Perry,Ellsworth, after an early Union Army casualty, Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth.

The Civil War continued into the next year, unexpectedly boosting the economy while taking more local men from home. When word came that young Dakota men in Minnesota had risen up against settlers, killing 200, there was disbelief and then, fear. One of the dead was Pierce County’s own Philander Prescott, a long time friend of the Dakota. Only the Mississippi River separated the traditional Dakota lands from the county, and the conflict could spread east. Little thought was given to root causes. Minnesotans fled to Wisconsin, and some Wisconsinites fled wherever they thought they would be safer. With much to fear from angry or terrified settlers, the few Dakota or Ojibwe in Pierce County made themselves as invisible as possible. It would take more than six months for the Minnesota perpetrators to be captured and county life could move toward normal.

In the eastern and southern states, the Civil War raged for three more years. War-related markets opened up to the betterment of Wisconsin, but the number of Pierce County military men also increased. By 1865, over 1,500 volunteers and draftees cited Pierce County as their residence, including ten African Americans. Some of these men might have come to the county to take the places of others willing to pay to avoid the draft. Still, nothing could prepare families and friends for the war’s casualties. At least 170 of the county’s soldiers were disabled, unknown numbers had invisible scars, and 200 died. Members of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry, known as the Iron Brigade, suffered the worst, having engaged the Confederates in battle at Antietam, Chancellorsville, Gainesville, Gettysburg, Wilderness, and the first Petersburg. Only 30 of Pierce County’s soldiers deserted.

Still, the county’s population grew by over 1,000 residents before 1866. The backbone of its economy was its wheat crop. The area’s rich soil had been producing prize winning varieties in increasing amounts for six years, and that bolstered other aspects of the economy. The county’s grist and flour mills were operating at capacity and Prescott was the county’s primary distribution funnel. In 1870, nearly 590,000 bushels of wheat passed through its facilities headed for markets up- and downriver. The docks were filled with farm implements.

Still, the county’s population grew by over 1,000 residents before 1866. The backbone of its economy was its wheat crop. The area’s rich soil had been producing prize winning varieties in increasing amounts for six years, and that bolstered other aspects of the economy. The county’s grist and flour mills were operating at capacity and Prescott was the county’s primary distribution funnel. In 1870, nearly 590,000 bushels of wheat passed through its facilities headed for markets up- and downriver. The docks were filled with farm implements.

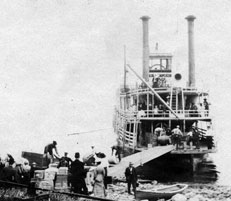

The end of the decade also brought township organization to completion. With the addition of Union, Salem, Rock Elm, and Spring Lake, Pierce County’s total reached 17. In addition, Pleasant Valley township became Maiden Rock, Deerfield became Gilman, and Perry became Ellsworth. The villages of Ellsworth, Prescott, Maiden Rock, River Falls, and Plum City were becoming cultural centers with schools, churches, hotels, theaters, newspapers, and organizations like the Freemasons, Woodmen, and Good Templars. Steamboats docking at Maiden Rock, Diamond Bluff, Trenton, and Prescott brought river trade and visitors to a western Wisconsin filled with optimism.

Through the next decade, the number of Pierce County residents climbed past 15,000. Much of the Big Woods had been cut and turned into lumber, and the cutover land, turned into farms. Though wheat prices were dropping, other conditions, products and services were shaping the future. Farmers were beginning to diversify their crops, raise stock, and experiment with dairying. The boatbuilding and fishing industries were strong along the Mississippi River corridor. And civic leaders in River Falls successfully wooed to the city a Normal School, Wisconsin’s fourth. Its doors opened to future Wisconsin teachers in 1875.

The last quarter of the 19th century was good to Pierce County. Transportation options increased for people and freight. The Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Omaha Railroad (The Omaha Road) linked the Wisconsin communities of Eau Claire and Hudson with St. Paul, Minnesota, and the Hudson and River Falls Railroad Company built a branch line between the St. Croix County and Pierce County cities. River traffic in Prescott quadrupled. Banks opened, business and real estate investors subsidized new ventures, and entrepreneurs continued to take business and development risks. A decrease in saw milling and small grist milling was balanced by an increase in flour and product milling (staves, panels, shingles, and wool). Small manufacturing and dairy processing increased, mining companies appeared, and more farmers worked smaller parcels more efficiently.

The last quarter of the 19th century was good to Pierce County. Transportation options increased for people and freight. The Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Omaha Railroad (The Omaha Road) linked the Wisconsin communities of Eau Claire and Hudson with St. Paul, Minnesota, and the Hudson and River Falls Railroad Company built a branch line between the St. Croix County and Pierce County cities. River traffic in Prescott quadrupled. Banks opened, business and real estate investors subsidized new ventures, and entrepreneurs continued to take business and development risks. A decrease in saw milling and small grist milling was balanced by an increase in flour and product milling (staves, panels, shingles, and wool). Small manufacturing and dairy processing increased, mining companies appeared, and more farmers worked smaller parcels more efficiently.

By 1880, the populations of River Falls and Prescott, as well as the townships of Ellsworth, Hartland, Maiden Rock, and Martell, passed 1,000 residents each. Ninety schools educated the county’s children, 18 Christian churches ministered to people’s souls, and traveling entertainers visited regularly. Four newspapers kept readers abreast of local, state, U.S. and International happenings. Two of them—the Pierce County Herald and the River Falls Journal—remain vital businesses. Before the turn of the century, the community of Spring Valley in Spring Lake Township would grow into a village of more than 700 people, most working in iron mining, smelting, and related businesses. Tiny Rock Elm Center in Rock Elm Township would double in size because of speculation on gold flour in the gravel of Plum Creek, and Elmwood would become more than a speck on the map.

Diversification held the key to the future. The Chicago, Burlington and Quincy  Railroad brought passenger and freight service to the Wisconsin side of the Mississippi River, linking Pierce County directly to markets in St. Paul, Minnesota, La Crosse and Chicago. Though bypassing the platted village of Trenton, the line prompted the organization of Hager City. It provided the people of Maiden Rock, Diamond Bluff, and Prescott with new job, market, and travel opportunities. The Omaha Road, now operating the line from Hudson to River Falls, extended service to Beldenville and Ellsworth, creating new shipping options to area farmers and retailers. A Minnesota and Wisconsin Railway line was being laid to link Spring Valley with the Omaha Road’s main line to the north in St. Croix County.

Railroad brought passenger and freight service to the Wisconsin side of the Mississippi River, linking Pierce County directly to markets in St. Paul, Minnesota, La Crosse and Chicago. Though bypassing the platted village of Trenton, the line prompted the organization of Hager City. It provided the people of Maiden Rock, Diamond Bluff, and Prescott with new job, market, and travel opportunities. The Omaha Road, now operating the line from Hudson to River Falls, extended service to Beldenville and Ellsworth, creating new shipping options to area farmers and retailers. A Minnesota and Wisconsin Railway line was being laid to link Spring Valley with the Omaha Road’s main line to the north in St. Croix County.

Road and bridge building, city and personal services, and farm supply and equipment sales increased. And, two new technologies wooed and won the county’s entrepreneurs. The first telephone call was received in Plum City before 1880. El Paso, Ellsworth, and Rock Elm investors formed a telephone company in the fall of 1888. A year later, a telephone line connected Ellsworth, the Omaha station, Martell, El Paso, Waverly and Rock Elm. Investors from southeastern Pierce County were close behind with the Union Telephone Company. Its line connected Maiden Rock, Union Panel Co., Plum City, Ono and Waverly, connecting at that point to the other company’s line.

In River Falls, plans were on the board to take better advantage of local water resources. An artesian well would be dug for a new municipal waterworks and the power of Junction Falls would be used to electrify Main Street. Twelve small communities appeared on the 1895 Atlas of Pierce County, Wisconsin, where none had appeared eight years earlier—Brasington, Exile, Farmhill, Herbert, Lawton, Lost Creek, Lund, Moeville, Olivet, Ono, Viking, and Waverly. When 1900 arrived, county growth and economic progress seemed unlimited.

Sources: Fifty Years in the Northwest, W. H. C. Folsom, 1888; History of Prescott, Wisconsin, Dorothy Ahlgren & Mary Beeler, Prescott Area Historical Society, 1996; History of Washington County and the St. Croix Valley; Rev. Edward D. Neill, North Star Publications Company, Minneapolis, MN, 1881; The History of Wisconsin, Vol. II: The Civil War Era, 1848-1873, Richard N. Currant, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, 1976; A Military History of Wisconsin in the War of Rebellion, E. B. Quiner, Clarke & Co., Chicago, 1866; The Wisconsin Frontier, Mark Wyman; Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis; 1998; History of St. Croix County, A. B. Easton, H. C. Cooper, Jr., Chicago, 1909; Atlas of Pierce County, Wisconsin, G.V. Nash & F. B. Morgan, Appleton and Oshkosh, WI, 1877-78; Atlas of Pierce County, Wisconsin, F.E. Lord & S. A. Carpenter, Ellsworth, WI, 1895.