Conflict over British and U. S. control of trade in Lower Canada, the Great Lakes region and the Upper Mississippi culminated in the War of 1812. A three-year series of confrontations ended with British defeat and a treaty in 1815 that led to negotiations over the boundaries between Canada and territory sought by the United States. Lieutenant Zebulon Pike’s land purchase of 1805 on the Upper Mississippi River would soon become the site of an important U. S. military post.

Completed in 1821 on a strategic bluff overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers, Fort St. Anthony was located in the proximity of several Santee Dakota villages. It became a trading post and jumping off point for travelers, hunters, and adventurers heading into the northwest wilderness. It also gave civilian entrepreneurs a base from which to plan the villages of St. Anthony (later Minneapolis) and St. Paul.

At least one European emigrant made a home on the eastern banks of the Upper Mississippi below the mouth of the St. Croix River. A Frenchmen fleeing insurrection in his native land is said to have settled and died in the Diamond Bluff area early in the century. But the first attempt at more extensive settlement was made in 1827 by U. S. military officers stationed at Fort St. Anthony, later named Fort Snelling. Before U. S. land was officially surveyed, claims amounted to nothing more than squatter’s rights. And even those were not allowed to military men. They claimed 1,200 acres anyway, near what would become the city of Prescott, asking a Indian interpreter and government supplier Philander Prescott to monitor it. The claim went unchallenged in court until 1841.

In that year, the U. S. government acted to reverse the 14-year “injustice” done to civilian land speculators by opening up the acreage up to new claims. It granted Philander Prescott ownership of 160 of those acres. He had overseen a trading post built in 1838 at what was then called “Mouth of the St. Croix,” and added 100 acres to his claim a few years later. He also tried to keep the remaining acres unclaimed, as was the military officers’ earlier intent, referring interested parties to lands farther north along the St. Croix River. Ultimately, this tactic failed.

The western boundaries of Wisconsin Territory changed several times before statehood. Most of the land had not opened to preemption because treaties with the resident Native Americans had yet to be negotiated. But pressure from representatives of expectant homesteaders mounted in Washington D. C. as unclaimed land in Illinois, Indiana and Michigan disappeared. The result was federal treaties with the remaining Ho-Chunk, Dakota, and Ojibwe in western Wisconsin Territory, negotiated and signed in 1837 and 1842. Terms of the treaties allowed the tribes to retain their hunting and fishing rights, while ceding all lands east of the Mississippi to the U. S.

Not many visitors, however, arrived to settle the far western Wisconsin wilderness in the next decade. Despite preemption, less than enticing weather and economic factors limited the influx of prospective landowners. The preferred settlement destinations lay west of the Mississippi. What was to become Pierce County largely remained a place of scenic interest to all but lumbermen. Though the first steamboats on the Upper Mississippi reached Fort Snelling before 1830, passengers, timber workers, machinery, and supplies didn’t move north on the St. Croix River until 1838. Still, enough people had settled near the river’s banks to populate a county. In 1840 St. Croix County was organized and it included land between the St. Croix and Mississippi rivers.

Timber surveyors began trekking up the county’s rivers and tributaries and entrepreneurs began to build mills and small, timber-related businesses on the larger waterways. Most importantly for the future Pierce County, Mouth of the St. Croix grew into a lively settlement. The Joseph Monjeau family joined Philander Prescott in 1839. Monjeau operated a ferry between the settlement and Hastings, Minnesota, and ran Prescott’s trading post in his absence. Swiss missionary, Samuel Dentan, held the first school sessions in 1843 and the George Schasers arrived in 1844. They built the settlement’s first frame house and produced the settlement’s first baby, Eliza. Not long after, in honor of the girl, Mouth of the St. Croix became known as the village of Elizabeth.

The population of southern and eastern Wisconsin Territory increased in the second half of the decade as immigrants, many of them from northern Europe, arrived looking for land. Statehood came in 1848, and with it, a change in the territory’s northwestern boundary, back to the St. Croix River. Newly surveyed lands brought a flood of prospective homesteaders to St. Croix County, many of them restless Yankees from New England and New York. Some arrived by steamboat, disembarking at Maiden Rock, Prescott, or Hudson. Others came from the southeast on foot, on horseback, and in wagons pulled by oxen. A road was cleared from Elizabeth north to the Kinnickinnic River and then 50 miles farther north to St. Croix Falls. Soon newcomers were clearing timber, building shelters, breaking soil, planting crops, and spreading the word to friends and relatives that new home sites awaited them.

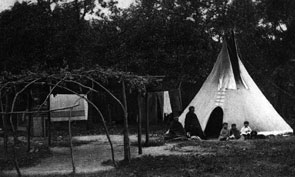

All this occurred while Mdewakanton band of Dakota and northern Ojibwe  hunted and camped in their traditional locations. No accounts of unprovoked attacks on the settlers of that time exist, but the enmity between the tribes was well known. Neither tribe could have predicted how their lives would change in less than a generation. It was but a few short years until the Yankees of northwestern Wisconsin were joined by Swedes, Norwegians, Germans, Bohemians, Austrians, French, Swiss, Scotts, and Irish emigrants. The rolling uplands, dramatic valleys, and clear running streams of the future Pierce County would remind many of them of home.

hunted and camped in their traditional locations. No accounts of unprovoked attacks on the settlers of that time exist, but the enmity between the tribes was well known. Neither tribe could have predicted how their lives would change in less than a generation. It was but a few short years until the Yankees of northwestern Wisconsin were joined by Swedes, Norwegians, Germans, Bohemians, Austrians, French, Swiss, Scotts, and Irish emigrants. The rolling uplands, dramatic valleys, and clear running streams of the future Pierce County would remind many of them of home.

An excellent description of a settler’s first years in the future Pierce County is found in the in the Reminiscences of Judge Joel Foster, published in the 1881 book, A History of Washington County, Minnesota, and the St. Croix Valley. Twenty-one-year-old Foster, fresh from fighting in the War with Mexico, took a Mississippi River steamer north from St. Louis in 1848, hoping to find a more healthful place to settle. He disembarked at Stillwater on the west bank of the St. Croix River, took a skiff south to Hudson, Wisconsin, and walked a trail about 20 miles southeast to the falls of the Kinnickinnic River. Choosing it for his new home, he returned to Missouri to plan his relocation.

An excellent description of a settler’s first years in the future Pierce County is found in the in the Reminiscences of Judge Joel Foster, published in the 1881 book, A History of Washington County, Minnesota, and the St. Croix Valley. Twenty-one-year-old Foster, fresh from fighting in the War with Mexico, took a Mississippi River steamer north from St. Louis in 1848, hoping to find a more healthful place to settle. He disembarked at Stillwater on the west bank of the St. Croix River, took a skiff south to Hudson, Wisconsin, and walked a trail about 20 miles southeast to the falls of the Kinnickinnic River. Choosing it for his new home, he returned to Missouri to plan his relocation.

Persuaded by his brother to return immediately to his desired claim, lest he lose it, Foster and a 20-year-old indentured African-American, Dick, caught the last steamer traveling up the St. Croix before the water froze for the winter. They built a rough cabin on Foster’s claim near Junction Falls and set about preparing for three months of snow and cold. Every 10 days, one of the men had to walk the 20 miles to Hudson, an old trading center on the Willow River where Foster stored supplies. The trip one way took about 14 hours in deep snow. In early spring, 1849, the two men traveled to St. Louis and returned with one plow, two cows, three dogs, four horses, 12 chickens, and seven dollars. They proceeded to clear seven acres of woodland and plant oats and potatoes, while living on venison, rabbit, fish, and bread. Despite hoards of biting black flies, they had broken 20 acres of prairie and built a large cabin by the end of summer. Dick, having completed his indenture, took out a separate claim and returned to St. Louis to find a wife.

Time on the land alone was hard for Foster, and harder when he learned that Dick’s friends had convinced him to stay in the south. His wife, they said, would be too isolated up north from friends and family, and so, they remained in St. Louis. Foster spent the next year at Junction Falls alone, working long hours, periodically joining the settlers in Hudson, and hoping for other settlers to join him The first serious homesteaders to arrive at Foster’s claim were the Mapes brothers, James and Walter. Foster convinced them that they couldn’t find a better place to start new lives. Not long after they staked their claims, the McGregor family arrived. While they lived in and improved Foster’s cabin, Foster assisted several other men in cutting a wagon road east to the nearest post office on the Eau Galle River, a distance of some 20 miles. Before long, the land near Junction Falls changed the way many locations across the county would, from a wilderness to a small community on its way to becoming a village.

Sources: Archeology of the Great River Road, John T. Penman, 1981; History of Washington County and the St. Croix Valley; Rev. Edward D. Neill. North Star Publications Company, Minneapolis, MN; 1881. Milwaukee Public Museum website, www.mpm.edu/wirp/;The Wisconsin Frontier, Mark Wyman; Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis; 1998.